The shortcut to this page is https://bit.ly/SJU-PHIL3000-CourseNotes

Course Notes and Resources

Module 1: Introduction to the Course 3

Explanation of the Course Content 3

A brief introduction to what this course is about. 4

The canon of “Western philosophy” 6

Module 2: Appearance and Reality: Are Things as They Appear? 8

Introduction to the readings on appearance and reality 9

Russell 9

Vasubandhu, Twenty Verses with Auto-Commentary 11

Bostrom 11

Resources: Videos and webpages 11

Russell 11

Berkeley 12

Vasubandhu 13

Bostrom 13

General Discussion of Appearance and Reality 14

Idealism. 14

Limited idealism/scepticism. 14

Science as showing our experience as largely mistaken. 15

So how do we evaluate these options? 15

Module 3: Topic: What Is There? 17

Yablo 18

Unger 18

Rosen 19

Maddy 19

Module 4: Topic: What Is Personal Identity? 19

Useful videos and websites on personal identity 20

Introduction to Personal Identity 21

Locke 22

Parfit 22

Swinburne 23

Williams 23

Module 5: Topic: What Is Race? What Is Gender? 23

Reading 23

Resources 24

Transgender 28

Haslanger 30

Spencer 31

(Notes on Elizabeth Barnes and Anthony Appiah to follow.) 31

Module 6 Topic: Do We Possess Free Will? 31

Quick Guide 32

On the philosophers we are reading: 33

Introduction to Free WIll Debate 34

AJ Ayer 36

Susan Wolf 37

Module 7a: Topic: Is Morality Objective? (Needs updating) 39

Introduction to the objectivity of morality 39

Module 8: Topic: What Is the Meaning of Life? 40

Introduction to the Meaning of Life 41

Notes on the readings on the meaning of life to come 42

Module 9: Topic: Autonomy and addiction 42

Readings. 42

General Discussion of Addiction 43

Notes on Readings to follow 47

Module 1: Introduction to the Course

Main points:

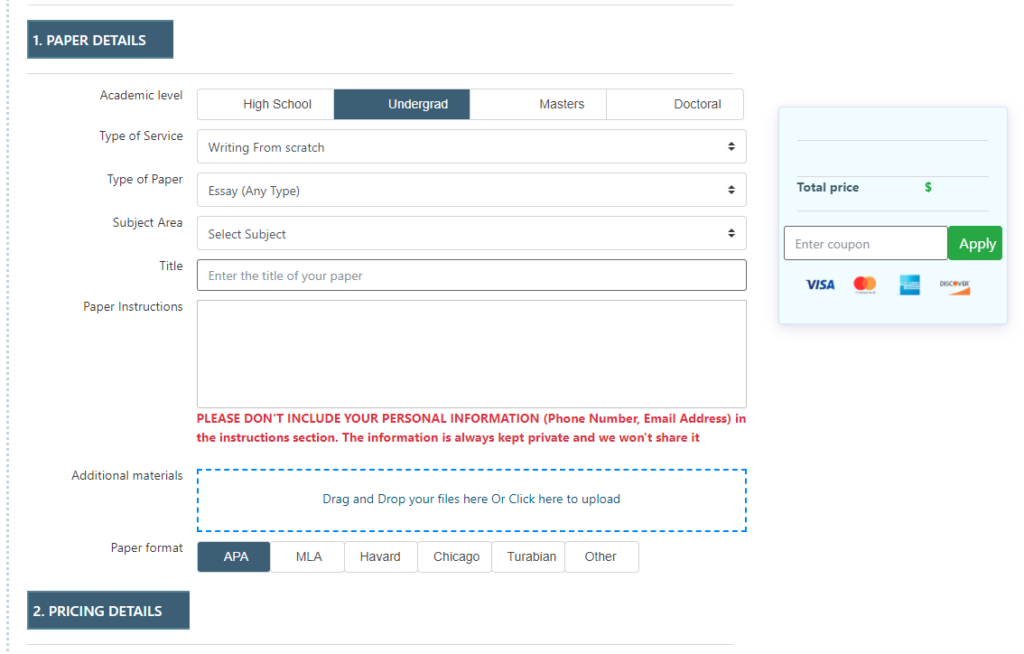

- Read the syllabus carefully.

- Follow the instructions in the Discussion Board for each week.

- Don’t miss any deadlines.

- If you do miss a deadline, make it up soon.

- If you have major problems and such as a medical situation that prevents you from working, then you need to get it documented in order to be able to submit work without penalty.

- Make sure all the work you submit is your own. Any quotations or sources of work that are not your own need to be carefully documented.

- If you cheat and get caught I will document the cheating and send the evidence to your Dean. You will get a 0 for the submitted work and maybe an F for the course, depending on my judgment. The F for academic dishonesty will remain on your transcript.

- If you are having problems with the work, you should communicate with me and say what those problems are.

Explanation of the Course Content

There are many approaches to teaching philosophy. I have taught this course at St John’s many times now, and I continue to evolve it. It presents several challenges. Most obviously, it is a Gen Ed course that students take because they have to rather than because they want to. So there is an issue of getting students to care about the course and find it useful in some ways. That generally means finding topics that can relate to student experience in some way, or inspiring students to care about very abstract topics with little apparent relevance to their lives and with no definite answers provided.

Second, there’s the issue of what background of knowledge students have. Being the third course of three in a philosophy sequence, it would be great to build on previous learning of students. But that’s not possible most of the time, because there is so much diversity in the ways that PHIL 1000 and the PHIL 2000 courses get taught in the Gen Ed sequence. There’s also the problem of students having short memories — even when they have studied relevant materials in previous courses, students seem to have little or no recollection of them.

Third, it is also relevant what parts of metaphysics I am enthusiastic about teaching. I tend to prefer a focus on recent debates in philosophy rather than going back to the history of philosophy for classic early discussions. I also favor topics that are relevant to science and ethics.

This semester for the most part, we will be using the textbook, The Norton Introduction to Philosophy. The readings have been edited down to more standard lengths, which makes it easier for students. The textbook also provides an introduction to each topic and questions about each reading which may be useful to students. It’s a bit of an experiment, and I will see how it goes. This is a big book, reasonably priced, although the pages are thin and the print is small. It is available in print and online formats. I will be interested to hear your feedback about it at the end of the semester. It’s a textbook that fits the needs of this course.

I would note that nearly all of the readings in the book are available online in some format if you use search hard enough and you use the library. But you will probably find rather different, unedited versions of what is in the book. If you are keen to see the full versions, or you don’t want to pay for the book, you can probably work it out, but you may well be making life harder for yourself. I do sometimes supply links to online versions.

There are many chapters in this book and I’ve selected the ones that are appropriate for this Metaphysics course. We are covering these topics:

- Consciousness

- Appearance and Reality

- Numbers and Reality

- Personal Identity

- Race and Gender

- Free Will

- The Objectivity of Ethics

- The Meaning of Life

- The Nature of Addiction

This overlaps with some more traditional courses in metaphysics, but does not address topics like the existence of universals (although we will discuss numbers), other worlds and counterfactuals, the nature of time, space and causality, the identity and persistence of ordinary objects, why the world exists, and the existence of God. We are including race and gender, the objectivity of ethics, the meaning of life, and the nature of addiction, all of which are somewhat untraditional in a metaphysics course.

While we will have some readings by the dead great philosophers from Ancient and Early Modern eras, there will not be many. Most of the readings are from the 20th century and many of the authors are still active researchers. We have rather more women authors than you find in many philosophy classes.

The readings are often challenging. You will need to read them two or three times to get a good understanding of them.

A brief introduction to what this course is about.

Understanding the western tradition of metaphysics comes best from the kinds of issues that get discussed. It is often said to be about the ultimate nature of reality, but it is far from clear what work the phrase “ultimate nature” does here. Certainly, the aim of many is in some way to go deep in analysis and somehow unveil the most fundamental secrets of the universe. But others deny that humans have the ability to do this, and some deny that the very idea of a fundamental nature of things makes any sense. So there are many kinds of debates within metaphysics, not just with competing theories about the nature of reality, but different theories about whether it is reasonable to try to understand the world in that way.

Metaphysical issues: here is a list of traditional topics in metaphysics.

- Does God exist?

- What is the nature of mind?

- What is metaphysical necessity?

- What is the nature of causation?

- What is the nature of time?

- What are persons?

- Do people have free will?

- Are there abstract objects?

- Are there other possible but non-actual worlds?

- How are different levels of description of the world related to each other (e.g. human life and atoms).

Metaphysics and science.

Metaphysics is about what exists. But, at least according to a common understanding, science also aims at finding out the fundamental nature of reality, so it seems that the two overlap. Yet metaphysics is done by philosophers by thinking in their armchairs, while science is done by scientists in their laboratories, or at least, that’s often how we think about the difference between them. It’s a philosophical debate and so there’s no generally accepted answer. A traditional view, probably taken by a majority of philosophers and scientists, is that metaphysics deals with non-empirical issues while science deals with empirical issues. (An empirical issue is one that can potentially be settled by observation or experiment.) On this view, a central metaphysical questions are whether abstract entities and universal entities like beauty, justice and the number 7 exist. It seems clear that these are not empirical questions. Of course, we can observe beautiful objects and we can observe cases of justice being done, just as we can observe collections of 7 objects. But that does not tell us whether there are separate abstract entities, “beauty”, “justice,” and “7.”

However, there are obviously some problems with this characterization of metaphysics. It looks like some metaphysical issues could be settled by observation. For example, we can imagine observing a god or great supernatural being. We can imagine observing souls and non-physical parts of mind. Furthermore, the modern science of the brain at least shed a good deal of light on the nature of the mind. It might even tell us whether we have free will. So it looks clear that science and metaphysics are not totally separate, but instead are interrelated in many cases.

In this course, we will spend a lot of time looking at how science and metaphysics are related, and we will address questions that are about the nature of reality, even though they are often not included in traditional metaphysics courses. Specifically, we will look at what counts as a mental illness, whether race is real, and whether gender is real. So we will look at how science interacts with our ordinary views of ourselves, whether a scientific view of the world can answer all the questions we have about the world, and what considerations beyond science are relevant in answering metaphysical questions.

You are free to argue for a different view, but the view I will be adopting for the purpose of this course, and also because I believe it, is that there is no sharp separation between science and metaphysics. Furthermore, I don’t just think there’s a grey area between the two. Rather, I would argue that at its heart, science contains deep metaphysical issues. (E.g., What is an atom, what is a proton, what is a quark, what is an electron? What are space and time? How should we categorize the objects in the universe?)

One might try to argue that science and philosophy are separate not because of their content but because they use different methods. It is true that philosophers tend not to do lab experiments. But these days philosophers do spend a lot of time interpreting the results of empirical research. It’s also important to note that many scientists are more theoretical than empirical, and do not work in labs. (Think of Einstein, for example.)

So a lot of this course will be involved with understanding and assessing what science says. That’s one of the reasons why we will not spend much time discussing this history of philosophy and supposedly “great philosophers of the past.” When you learn about science, you generally learn about recent science, and similarly, for this course, we will spend most of our time studying recent philosophy. It will be useful sometimes to learn about past thinkers, and we will do that early in the course. But the majority of the course will be about recent work and on issues that are of contemporary interest.

I’m excited about this course: it is always interesting to learn what students think and to engage them in the topics.

The canon of “Western philosophy”

There has been plenty of debate about the “canon of philosophy” over the years. There is a familiar list of names: Plato, Aristotle, Augustine, Aquinas, Locke, Berkeley, Hume, Kant, and Hegel are normally included. There are many other figures who sometimes get mentioned.

Sometimes they get referred to as “dead white men.” It is definitely true that they are all dead and all men. “White” is a bit more problematic. Augustine was from north Africa and is generally thought to have been a Berber. It is also important to understand that our current racial categories are fairly recent, and would not have made a lot of sense in the ancient world.

The fact that there are no women on the list is a reflection of the fact that in most societies of the past, women were not given the freedom to study and set out philosophical ideas. Furthermore, if women did engage in philosophy, their work was much less likely to be recorded, and if recorded in some fashion, it was more likely that their work would be destroyed or forgotten. There are occasional references to the work of women in the history of philosophy, and sometimes we have records of what they said. Generally though, that work is fragmentary. There are some cases of work by women in the history of philosophy, more in recent centuries, and there is now significant effort being made to recover their writings and to give them more prominence.

There is the issue of “non-Western” philosophy. The “Western” canon is based on the work of European men. The Europe of the “Western” tradition actually extends quite far east into West Asia. During the middle ages, the tradition of Plato and Aristotle was saved and extended especially by Islamic scholars during the “Golden Age of Islam.” While there’s often little acknowledgement of this, the work of scholars such as Avicenna (Ibn Sina) and Averroes (Ibn Rushid) probably had a significant effect on early modern philosophy.

But even taking the diversity within the “Western” tradition into account, it is true that it does not include work by thinkers of the Far East or Africa, for example. There is some debate over where philosophy starts and religious thought ends, and whether the work of other traditions strictly counts as philosophy. But the “Western” tradition includes plenty of religious thought and theology, so to insist that other traditions are not strictly philosophy seems to make a rather artificial distinction. It does seem that there was not a great deal of interaction between “Western” and “non-Western” traditions at least in ancient times.

Some approaches to teaching philosophy try to be inclusive of more traditions, and might reject the label of “Western” philosophy, opting for “World” philosophy instead. It is certainly interesting to see the overlap of ideas in different traditions. One challenge this presents is the effort required to interpret texts of different traditions, which come with different sets of assumptions and require different background information. To go broad in this way tends to mean that one increasingly feels one is merely scratching the surface of the issues. In this course, there are only a couple of places where we look at “non-Western” approaches. It may be possible in the future to be more diverse in the approach of this course, but the change is gradual.

Another problem with the canon of “Western” philosophy is that the “great” philosophers held many views that we now not only reject, but regard as terrible . In particular, many supported slavery, colonialism, and the oppression of women. Often this was not just a matter of their private opinions, but rather, they defended their views in their work. Aristotle is notorious for his advocacy of “natural slavery.” He also argued that women are inferior to men. Hume claims that other races are inferior in important ways. Kant seems to argue that women are morally deficient and that non-Europeans are incapable of the heights of thought Europeans can reach. (To be fair, Kant did eventually reject colonialism and slavery, but he was in his 70s when he changed his mind. It was long after he wrote his major works.)

Of course, these views were very common in the societies in which these philosophers lived, and often it is pointed out that it is anachronistic to hold them up to the moral standards we use today. These canonical philosophers were highly influential for the history of philosophy, and any serious student of philosophy at least needs to be aware of their work. Many contemporary philosophers find great philosophical richness in coming to understand their reasoning and studying their writing.

Nevertheless, there’s a question about whether it makes sense to require undergraduates who will probably never study philosophy again to read the work of these canonical philosophers who held such problematic views. Should we hold them up in praise as “the most important thinkers”? I tend to take a compromise position, acknowledging the historical importance of these philosophers, but balancing that with a heavy dose of more contemporary philosophy. That has the advantage of being written in more contemporary English, and it is possible to include more female philosophers. When studying the work of the canonical philosophers, it is important not to gloss over their problematic views, but instead to highlight them and to consider how they may have fit with the rest of their philosophical systems. The project of teaching philosophy involves helping students to be critical of many widely accepted views, so see if they can stand up to serious scrutiny. So it is fitting to apply that critical attitude to the works and reputations of the “great” philosophers too.

Useful videos

The word “metaphysics” gets used in different ways by different people. So if you search for metaphysics on YouTube, you will find all sorts of strange videos about mysticism and new age thinking. So you have to work fairly hard to sort out which videos are actually about the tradition of metaphysics in Western Philosophy. Here are some. You can get bonus points for finding others, summarizing them and maybe also discussing them.

Academy of Ideas. Introduction to Metaphysics. 8 minutes. https://youtu.be/qKq0Afmsj-U

Using what seems like Prezi software, the speaker (who isn’t identified) gives a quick overview of the field.

Joseph Kraft: “What is Metaphysics?” 8 minutes. https://youtu.be/ja_tIGpwzPE

This short video gives a short overview of some of the central themes in western metaphysics.

Marianne Talbot: Oxford University Department for Continuing Education. “Metaphysics and Epistemology.” 74 minutes. https://youtu.be/uy8UGPxpCGs

This lecture spells out some of the ideas of metaphysics, ontology, and epistemology.

Talbot manages to do 74 minutes with 3 slides. The video ends abruptly in mid-sentence, but it was probably close to the end anyway.

Module 2: Appearance and Reality: Are Things as They Appear?

| Bertrand Russell, APPEARANCE AND REALITY (NIP p.410 or CHAPTER I ) George Berkeley, Three Dialogues between Hylas and Philonous (NIP p. 416 or Three Dialogues between Hylas and Philonous in opposition to Sceptics and Atheists ) Vasubandhu, Twenty Verses with Auto-Commentary (NIP p. or Vasubandhu Twenty Verses ) Nick Bostrom, ARE YOU LIVING IN A COMPUTER SIMULATION? (NIP p. 442 or Are You Living in a Computer Simulation? ) |

Introduction to the readings on appearance and reality

The theme of appearance and reality will be familiar by now since we have covered various approaches to skepticism and the worry that our knowledge of the world is minimal, and that the world is very different from how it seems to be. These are 4 very different approaches to the topic.

Russell was a famous philosopher of the twentieth century and he argues for a reasonably “common sense” view. Berkeley was a philosopher with strong religious views who argues that reality is very different from what most people think it is — he says there is no matter in the world, and everything we experience is no more than an idea. Vasubandhu comes from a Hindu tradition, and argues for an idealist view of the world similar to Berkeley’s. Finally, Bostrom argues that we may be something like brains in vats controlled by intelligent computers.

Russell

Russell was a famous philosopher of the twentieth century and he argues for a reasonably scientific “common sense” view. Berkeley was a philosopher with strong religious views who argues that reality is very different from what most people think it is — he says there is no matter in the world, and everything we experience is no more than an idea. Vasubandhu comes from a

Hindu tradition, and argues for a mystical view of the world. Finally, Bostrom argues that we

may be something like brains in vats controlled by intelligent computers.

This piece is covered a lot in intro courses. You can find summaries on Study.com and sparknotes.com, for example. It is from his book Problems of Philosophy, which was the first philosophy book I ever read, I think. One of the most important parts of it is that Russell uses the idea of sense-data. This is a way of referring to your experience of sensing things. The assumption is that your experience can be broken down into its component parts, which are little bits of experience (data). It is a plausible idea. We are used to the idea that a TV screen is made up of dots of different colors which can change rapidly, and a painting is made of paint on a canvas, a sum of thousands of different brush strokes of different colors. A piece of music can be digitized and put on a computer. And our experience is definitely related to how our sense organs (eyes, ears, skin, nose, tongue, etc) are stimulated, and these generate signals in the brain.

Nevertheless, there has been a great deal of debate over the years about how to understand sense-data and whether it makes sense to take an atomistic approach to our experience, as if it were composed of small building blocks. Many people have argued that it is at least more complicated than that, and that our experience is holistic in some way. The work of gestalt psychologists on figure and ground is often cited. The central point is that the arrangement of light and dark and the colors don’t determine our experience. With some figures and maybe all, our experience comes embedded with concepts in some way. Take a look at these: https://images.app.goo.gl/qtibw69rWBUY9QRy8

The “sense-data” don’t change, but still your experience of what you are seeing can change as you shift. This highlights the idea that a lot of visual experience is of objects in the world seen as those objects. What they are is part of the experience — it is not added on after. So if I look at a chair, I am not seeing sense-data, and my experience does not just consist of sense-data. Rather, my experience is of the chair. The “chairness”, whatever that is, is part of the experience. Sometimes this has been explained as the idea that all seeing is “seeing as…”

George Berkeley

Berkeley is often grouped with the other British empiricists Locke and Hume. He shares with them some empiricist theories about how we gain knowledge, and he has a similar view of the mind (the theory of ideas.) But in other ways his theories are very different from those of Locke and Hume. Their approach relies very little on any idea of God, while Berkeley’s view has God at its center, holding everything together.

Berkeley has a radical view about reality: the world does not exist as we think it does. He thinks there is no such thing as matter, and indeed that the whole idea of matter as something that exists independently of us is very confused. The only things that exist in the world are God (and maybe angels), and human spirits. God gives everyone their experience of the world. We get our experience with our “ideas” which are our sensations. But they are not sensations of anything outside of ourselves, because there is no physical world.

This might seem that God is deceiving everyone. That would be a tricky claim for any good Christian, because deception is bad. Berkeley’s solution to this is surprising: he denies that regular people think that there is such a thing as matter, so God was never deceiving them. He suggests that only philosophers made the claim that there is such a thing as matter, and they did this because they got confused. On his view, most regular people only believe that they experience their own ideas, and make no metaphysical claims beyond that.

Some days I wonder why anyone takes Berkeley seriously. It seems to be obviously wrong both about the existence of matter and people’s belief in matter. But what makes his view interesting is that he has an argument that is hard to get out of, and his view has been historically important. While not the first defender of “idealism” — the theory that the world is just made of ideas — he is one of the most significant ones, and some philosophers have had views which are actually quite close to idealism. (On some interpretations, Kant is one of them.)

A note on the text of the Three Dialogues. The version in the textbook is about 11 pages. The online PDF is 65 pages. The textbook version is a slightly modernized version of the 1713 text, while the PDF is more like a translation into modern language. Those using the PDF might want to ask some questions from others about what parts of the dialog are used in the textbook.

Philonous advocates for Berkeley’s position, while Hylas is the initially unconvinced dialogue partner.

Vasubandhu, Twenty Verses with Auto-Commentary

Vasubandhu was an Indian philosopher monk from the 4th or 5th centuries. He was one of the most important philosophers for Buddhism. He argues for something like idealism, similar to the views of Berkeley. As it says at the beginning, everything is nothing but appearance.

We see Vasubandhu reply to various objections to his idealism. A lot of this is quite difficult to understand, but it is possible to get the general idea. He seems skeptical about a lot of knowledge, saying that we don’t know our own minds or other people’s minds.

Bostrom

There are lots of videos explaining Bostrom’s argument. There are web pages too. So it is easy to find summaries of the main ideas, which is good since it looks technical, even though it is not really so bad.

As with Berkeley, many of us are pretty confident that he must be wrong, though some may be open to the possibility that he could be right.. But if he is wrong, then where is the fault with his argument? That’s the main thing to discuss.

Resources: Videos and webpages

Russell

3 mins Animated with voice over.

12 mins. HaugenMetaphilosophy Guy talks to camera next to river.

Webpages

- Bertrand Russell on appearance and reality – Ask a Philosopher

- The Laws of Figure/Ground, Prägnanz, Closure, and Common Fate – Gestalt Principles (3)

Berkeley

Locke, Berkeley, & Empiricism: Crash Course Philosophy #6

10 mins.

6.1 Introduction to Primary and Secondary Qualities

Peter Millican lectures, 15 mins

Berkeley’s Idealism | Philosophy Tube

8 mins. Guy talks to camera

Peter Millican lectures 10 minutes

Podcast

George Berkeley – The Great Idealist

47 mins 3 philosophers discuss and explain the theories.

George Berkeley: Dialogues between Hylas and Philonous

9 mins.

This is a computer-voice version of the Dialogues. It does not seem very close to the text, but it gets the main ideas.

6.1 Introduction to Primary and Secondary Qualities

Peter Millican lectures, 15 mins

Berkeley’s Idealism | Philosophy Tube

8 mins. Guy talks to camera

Peter Millican lectures 10 minutes

Podcast

George Berkeley – The Great Idealist

47 mins 3 philosophers discuss and explain the theories.

George Berkeley: Dialogues between Hylas and Philonous

9 mins.

This is a computer-voice version of the Dialogues. It does not seem very close to the text, but it

gets the main ideas.

Vasubandhu

Video

Paving the Great Way | Robert Wright & Jonathan Gold

67 mins. Interview with expert.

Webpages

Bostrom

Nick Bostrom – The Simulation Argument

23 minutes. Interview.

Sam Harris and Nick Bostrom – Are You Living in a Computer Simulation

From a podcast 5 mins.

The Simulation Argument

3 mins. Animated.

Are We Living in a Simulation?

Sort of a talk show. 7 minutes

2016 Isaac Asimov Memorial Debate: Is the Universe a Simulation?

2 hours.

Are We Living Inside a Computer Simulation?: An Introduction to the Mind-Boggling “Simulation Argument”

52 mins documentary

Webpages

- The Simulation Argument – Bostrom

- Opinion | Are We Living in a Computer Simulation? Let’s Not Find Out

- Ancestor Simulations | The Psychology of Extraordinary Beliefs

General Discussion of Appearance and Reality

This module covers a lot of ground. There are many ways to frame the question of the relationship between appearance and reality. Let’s list a few:

- How much can we trust our senses? Does the way the world looks match the way it is?

- Is it possible that our senses are largely mistaken and we are being deceived about the world around us? Are there grounds for scepticism?

- Does science tell us the whole truth about the nature of reality? Are there aspects of reality revealed in our experience that cannot be described by science?

- What is the nature of our everyday experience of the world? What does it tell us? Are we perceiving objects external to us as many philosophers such as Locke assume, or are we just aware of own perceptions and nothing else, as it seems that Berkeley believes?

- Can extra-ordinary experiences such as revelations, hallucinogen-induced trips, or near-death experiences provide us with knowledge of other realms of reality?

There are also a number of theories about the relationship between appearance and reality.

Common sense realism

We learn about the world through our senses. While it is possible for our senses to malfunction (deficits such as blindness or deafness, or illusions that can lead us astray) for the most part our senses tell us enough about the world in order for us to function. That is why they evolved. They may not tell us everything about the world and we can develop technology to enhance our ability to detect objects (with microscopes, telescopes, infrared light vision, for example.) Science can explain our experience but does not reveal that our experience is fundamentally mistaken, although it may correct some mistaken beliefs about our experience. John Locke is the best representative of this view.

Idealism.

This view is that there is a fundamental mistake in the assumption of a physical reality independent of human beings. It says that we are aware of our perceptions (or ideas, as Berkeley called them) and there is no physical world independent of our ideas. It says that the theories about the nature of matter that science has given us should not be taken as describing an independent reality, but rather is merely a way of predicting our future experiences. The big question for idealism is how come science is so successful if it is not literally true? Berkeley’s answer is that God has arranged the world that way. Our perceptions operate in predictable ways as if there were an independent reality but in fact God is arranging everyone’s perceptions to coordinate with each other.

Limited idealism/scepticism.

- Descartes in his meditations raises the possibility that he is being deceived by an evil demon and that all his perceptions about the physical world are mistaken. It is silent on the question of whether there is any physical world.

- In The Matrix we see a world in which nearly all humans are systematically deceived about the nature of reality. They live in a virtual reality which falsely depicts how the world is. But there is a real physical world.

- Nick Bostrom raises the possibility of a different kind of mistake, where all the humans we are aware of exist as simulations in a computer. In Bostrom’s scenario, there is a physical reality somewhat similar to what we experience, but are not directly experiencing it. We are experiencing a simulation of the world as it used to be and we don’t have any physical bodies that are experiencing the world. Bostrom is not endorsing this, but he does raise it as a possibility.

Kantian idealism.

On this view ultimate reality (the noumenal world) is completely hidden from us, but there is a shared intersubjective reality the form of which is imposed by our own psychology. So the laws of science are true not so much because they describe the world accurately, but because they describe a phenomenal world that is a product of the interaction between the noumenal world and human perception systems. It is a mistake to think that science describes ultimate reality, but it does accurately describe a kind of intermediate reality. It is not subjective because it is a shared nature that all humans have. Indeed, Kant thought that it is a shared nature of all rational creatures. Our ordinary experience reveals that intersubjective reality.

Science as showing our experience as largely mistaken.

Some people argue that science shows that our ordinary perception of the world is mistaken. For example, it says that the world is made of atoms with large gaps between them, but we see the world as made of solid objects. Or that the world is really all just made of energy and fields, but we see it as made of solid objects.

So how do we evaluate these options?

We might think we can easily eliminate Berkeley’s proposal since it relies on the assumption that God is busy coordinating everyone’s experience. We have no evidence for the existence of a God who does that, and it seems a much simpler and better explanation of our experience to assume that there is an independent physical reality that causes us to have a shared experience of it. This seems basically right to be, but we should note that Berkeley does present the challenge of explaining how we can understand anything beyond our experience. He says we only have our experience and so it is impossible for us to even imagine something that it outside of our experience (or something like that — he does think we can imagine souls and God, so his theory must be more sophisticated than I have sketched it.) The philosopher David Hume took Berkeley’s view and ran with it — he argued that we cannot understand anything beyond our experience and we should stop trying to figure out the ultimate nature of reality. He was impressed that science can deliver useful results but we should not think that it gives us the truth. Kant’s idealism was a direct reaction to Hume’s challenge.

A defender of Berkeley’s view might question why it is better to explain our experience by saying that there is physical matter that causes our experience rather than a God who arranges it all. They might say that we have no independent evidence that physical matter exists, outside of our experience. So there’s no more reason to believe that matter exists than God. I’m not sure that’s true, but and it would take some further defending and explaining to unpack it fully. But even it were true, it still strikes me as a better explanation of our experience to say that it corresponds to how things are in the physical world rather than that God is arranging it all. God seems very busy on this view, in an epic effort of multitasking, making sure that everyone perceives the same world even though it does not correspond to any physical reality. We might also wonder why God makes the world of experience obey laws of nature applying to physical matter if there is no physical matter. If God is so busy creating experience, then the problem of evil (why does God allow great preventable suffering) is all the more pressing.

If we can eliminate the Berkeley view, then we still have several options to evaluate. They all seem like going options still defended by some philosophers, so that’s an ongoing debate. We have to see how different philosophers defend their views.

I would divide the debate into two parts, associated with different questions.

- How do we answer sceptical worries?

- How do we know our understanding of reality is right?

For the first question, we may just have to accept that we can never fully settle worries about massive error and deception. It may be that I am a brain in some mad scientist’s lab and the scientist is inputting all my experience. But just because that’s a possibility does not mean that it is a probability or one that we need to take seriously. We may not even have a basis on which to assign probabilities of our being massively wrong. Nevertheless, unless there is a way to actually investigate the possibility of error (as Neo does in The Matrix) then it seems pointless to worry about it.

The second question provides a more fulfilling project of investigation. What parts of our understanding of reality can be thrown into doubt even assuming that our basic beliefs about the world are right? Common sense realism has, from the time of Locke, maintained that color properties are not real, but are as much dependent on the observer as is smell, and they are a product of the interaction between the world and the human brain. Locke made a distinction between primary and secondary qualities of matter. He said that our ideas of the primary qualities — the fundamental properties of matter — are accurate. We know those properties. Locke said that the fundamental properties were size, shape, motion, and hardness. Obviously we would have a different list today. But whatever the list, we can still make a distinction between primary qualities and secondary qualities. The point is that our ideas of secondary qualities, color, smell, feel, taste, sound, and maybe others do not resemble the actual qualities that cause those ideas.

Locke’s view is very plausible but it needs updating because modern physics is very different from the physics of his day. Our understanding of primary qualities — the fundamental properties of matter, and indeed, the whole concept of matter — is extremely different now. We have concepts of fields, wave-particle duality, infinitesimally small particles, multiple dimensions, and gravitational waves, for example. Arguably, at the most fundamental level, all we have is a mathematical formalism that is stripped of any connection to ordinary experience. So it is far from clear that Locke’s theory of primary qualities is sustainable, and his claim that we can understand the nature of matter in some transparent way seems up for debate depending on a philosophical scrutiny of modern physics. We might be pushed toward a more Kantian view that while we have a way of understanding the physical world, we do not really understand the ultimate nature of matter, and our scientific theories are better understood as a form of intersubjectively agreed rules with which we can predict the results of experiments.

Module 3: Topic: What Is There?

Useful resources

Platonism in the Philosophy of Mathematics in SEP: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/platonism-mathematics/

Also see related SEP articles on abstract objects | mathematics, philosophy of: indispensability arguments in the | mathematics, philosophy of: naturalism | physicalism | Plato: middle period metaphysics and epistemology. Links at bottom of article.

Philosophy Talk: What are numbers? https://www.philosophytalk.org/shows/what-are-numbers

Podcast: What are Numbers? Philosophy of Mathematics. https://youtu.be/xXD57a5BEO0

We Love Philosophy blogpost: https://welovephilosophy.com/2012/12/17/do-numbers-exist/

Introduction to “What There Is”

STEPHEN YABLO, A Thing and Its Matter 461 (Available here if you sign in)

PETER UNGER, There Are No Ordinary Things 467 (Full article available though SJU library)

GIDEON ROSEN, Numbers and Other Immaterial Objects (Only available in book) 476

PENELOPE MADDY, Do Numbers Exist? 485 (Available here if you sign in)

These articles address some of the most difficult issues in metaphysics, but three of them are specially written for undergraduates, and so are more easily accessible. The Unger piece is cut down in size from its original 38 pages so that is also made more accessible for students.

Unger and Yablo both discuss our understanding of ordinary objects. Yablo discusses how we count objects and how many things there are, while Unger argues that our regular understanding of ordinary objects is deeply mistaken and in fact there are none as we understand them. With this type of philosophy it is tempting to think that the philosophers are taking language too seriously and are trying to be rigorous where rigor is inappropriate. But this kind of philosophy is not so easily dismissed. If we can’t make sense of our basic concepts then that starts to throw our whole use of language into doubt, and then most of our ordinary practices might be unjustified. (Note that Unger likes provocative conclusions: he has also written a paper entitled “I do not exist.” His general view is what he calls metaphysical nihilism. He also has argued that there are no people (see his article here). Yet he also thanks various people at the end of his paper for their help in developing his ideas. Is this a self-contradiction?)

Yablo

Yablo is a professor at MIT. In this short piece, he ex;ains the pluralist claim that a penny is a different thing from the copper than constitutes it. He comes up with arguments for this claim and defends it against some criticisms. Obviously this is a view that goes beyond pennies: it applies to all objects and the material that they are made of. He contrasts pluralism with monism, which says that the penny and the copper are the same thing. Then he shows how the debate between pluralism and monism can play out. He does not claim to settle the debate: rather he is showing the way that monism and pluralism appeal to differing intuitions. He also raises the question of how we decide which intuitions to take seriously and suggests that sometimes they can be dismissed as irrelevant.

Note that Yablo assumes that there must be a right answer to the question of how many objects there are in the box. Some might be inclined to doubt this assumption. We might be inclined to say that it all just a matter of convention or perspective. How many items we count could be just subject to the context and the purposes of our interests, and there might be no deep answer to “how many items are there in the box really?”

Conventionalism and perspectivism are pretty attractive positions when it comes to counting pennies. However, you might hesitate when expanding the view to counting people. Is it just a matter of convention whether you are the same thing as your body?

Unger

Unger is a professor at NYU. His article here uses a “Sorites paradox” or as Unger describes it, an argument. (Here is a useful 5 minute video about it.) It is an argument that a heap does not exist. It is an interesting argument, but one that most people find unconvincing. Most of the philosophical debate is in working out what is wrong with the argument. But Unger goes with it, and accepts the conclusion. He then uses it to argue that that there are no ordinary objects.

———–

Rosen and Maddy discuss the existence of numbers. Rosen argues that they exist as abstract objects, while Maddy argues that there is no more to numbers than the properties of groups of objects. One might extend this debate to the existence of geometrical figures. Plato postulated the existence of a realm of forms where the perfect ideas existed for geometrical entities– circles, squares, etc. Plato’s realm of forms seems like an extravagant suggestion and he provides no explanation of how humans interact with it. We might wonder whether Rosen’s postulation of abstract objects is any less extravagant or explanatory. One of the remarkable aspects of mathematics is how much knowledge there is of it — all its different branches and subbranches. It is very tempting to suppose that we are discovering truths about some independent realm, rather than just learning about properties of objects.

Rosen

Rosen is a professor at Princeton University. He considers whether the existence of numbers is compatible with physicalism. Physicalism says that everything in the universe is physical. It raises the question of what we mean by a physical object. Rosen does not say much about this: he gives a list of physical objects: a book, a window, a tree, an atom and a black hole. Physical objects are like those. He also says that physical things are those that can be completely described in the language of a perfect physics. [But can we capture everything about a book in the language of physics? This may not be a big issue. His argument may not depend on a good definition of physicalism. ]

He argues against physicalism, considering various moves in the debate over whether physicalism is compatible with the existence of numbers, and gradually developing his case. His main point is that numbers are abstract objects, and abstract objects cannot be physical objects. He summarizes his main argument finally in section 8. Note that he does not really provide an alternative account of the nature of numbers or how we know about them. He is just arguing that physicalism cannot be the answer.

On the way to his conclusion, Rosen considers a number of counter-arguments to his view. The best counter-argument is in his section 5, which advocates a kind of instrumentalism: we can talk as if numbers exist but it is just a way of talking about the world. We can talk as if numbers exist and we can do arithmetic, but we don’t need to believe they really exist. Rosen does not say this is necessarily wrong, but he argues that it is the job of the person making this argument to show how arithmetic could be true if numbers don’t exist. He argues that the instrumentalist argument is a sceptical argument and those advocating it have the burden of proof to show that it really works.

Section 7 also advances an interesting argument against abstract objects. It says that in order for us to know about an object we have to interact. (Causal requirement for knowledge). But we can’t interact causally with abstract objects, so we can’t know about them. So we have no reason to think they exist. Rosen’s reply is to reject the causal requirement. He argues that we must be able to come to know about abstract objects in other ways. [One might respond that he has the burden of proof to come up with a way we know about abstract objects.]

Maddy

Maddy is a professor currently working in the UK, though originally from the USA. She is not convinced by arguments like those provided by Rosen, and defends that plausibility that numbers are no more than properties of groups of objects. This is a version of nominalism about numbers. If there are 3 apples on a table, then this is just a number property of the group of apples. That does not mean that the abstract object “3” exists.

If we take this view, then can we explain all the distinctive features of arithmetic, without supposing that any abstract objects exist? As she explains, arithmetic now uses concepts like “infinity” which is harder to map onto an actual group of physical objects. It seems that we are using our imagination and are reasoning more hypothetically. But when we are discovering arithmetical truths that don’t seem to correspond to objects in the world, what are we finding out about? Maddy’s answer is that we are not finding out a different realm at all. She says they are descriptions of “this shared human picture implicit in the psychological mechanisms that underlie our capacity for language.” (489)

On the last couple of pages of Maddy’s article, she goes one step further. She argues that it is probably a mistake to think that there are even two different theories competing with each other. She suggests that the theory of abstract objects is just another way of describing the physical world. It seems she thinks that the theory does not even succeed in proposing an alternative view of the world. Her comments are short and depend on an analogy from chemistry, so they are a bit cryptic. She does admit that most philosophers will regard her view as heresy.

Module 4: Topic: What Is Personal Identity?

Readings

Introduction

JOHN LOCKE, Of Identity and Diversity, from An Essay Concerning Human Understanding 505 (This is available open access in several places on the Internet. Here is one.)

RICHARD SWINBURNE, The Dualist Theory, from Personal Identity 513 (Available here in longer and maybe different form)

DEREK PARFIT, Personal Identity, from Reasons and Persons 520 (Available here)

BERNARD WILLIAMS, The Self and the Future 533 (Available here in longer form)

Useful videos and websites on personal identity

There are plenty of videos on YouTube about Locke’s memory theory of personal identity.

1. 2 minute video narrated by Gillian Anderson. Narration over illustration.

(I’m still getting used to Anderson’s English accent.)

Locke on Personal Identity. Michael Della Rocca from Yale gives a lecture with animated illustrations. (He seems to bang his desk a lot.)

This is part 1 and is about 12 minutes. Part 2 is a bit longer. Part 3 is about 10 mins.

Personal Identity: Crash Course Philosophy #19

An energetic guy called Hank sits at a desk and talks but there are also illustrations. 8 minutes.

It covers both the body and memory theory of personal identity.

He covers the Williams thought experiment.

Arguments Against Personal Identity: Crash Course Philosophy #20 . 10 minutes.

In this one, Hank includes Hume’s skeptical theory of personal identity and Parfit’s theory.

2. Derek Parfit discussing personal identity in the documentary Brainspotting

9 minutes.

10 minutes.

3. Personal identity, Part I: Identity across space and time and the soul theory

Shelly Kagan lecturing at Yale. 50 minutes.

This is followed by 3 other lectures on the topic.

4. Interview with Eric Olson

2 hours skype interview.

It is rather dry but it gets into the distinctive features of Olson’s views. He sometimes relies on ordinary intuitions and at other times dismisses ordinary intuitions. Ultimately, he is trying to find a way of representing our ordinary thought that make sense of them. He very much relies on the distinction between essential and accidental properties. Some of the discussion of corpses is illuminating.

5. Eric Olson: On Parfit’s view that we are not Human Beings (RIP, 01/11/2013)

51 minutes lecture. Olson argues against recent arguments by Parfit.

6. Shelly Kagan.

http://oyc.yale.edu/philosophy/phil-176/lecture-11

Lecture 11 – Personal Identity, Part II: The Body Theory and the Personality Theory

50 minute lecture. You can skip the section 2 of the lecture by clicking on the appropriate link. It starts in the 3rd minute.

Let me know if you have problems with the links.

Introduction to Personal Identity

The literature of personal identity is full of thought experiments — these are imaginary scenarios designed to elicit reactions from you, in order to show problems with a philosophical theory, or to show how a different philosophical theory can match those reactions. We will see examples of people being separated from their bodies, people waking up with different memories and self-beliefs, brains being taken and put into another body, a brain being divided into two put into two different bodies, teletransporters where a body is destroyed thought being completely analyzed, converted into energy or information, and then reconstituted in a different distant location. Science fiction is full of such examples. They push us to imagine what is logically or conceptually possible — not what is physically possible. They are meant to be helpful.

The use of thought-experiments is common in much of philosophy — ethics is a clear example. But it has been especially heated in debates about personal identity, and it has led to reflection on how seriously we can take thought-experiments as a guide to philosophical truth. The article by Bernard Williams is especially good on this — he points out how our reactions, or intuitions they are often referred to, can change depending on how we narrate the thought experiment, varying the point of view from which it is told.

Locke

First, a little bit about Locke. It should be pretty easy to find summaries of Locke’s views on personal identity using a search engine. I provide a couple of links to videos above. Locke’s view is simple: what makes you who you are is your consciousness, and so if you can now remember an event in the past, say a year ago, then you are the same person as the person who had that experience. Locke does not endorse any theory of consciousness, since he thinks it is mysterious. He does not understand how a brain could create consciousness, but equally he does not understand how an immaterial soul could do it. So he does not endorse a soul theory or a brain theory of personal identity. His view is, however consciousness works, it is consciousness that makes us who we are.

Locke’s theory has plenty of intuitive appeal. But it also has lots of problems. First, there are details that need filling out. What does he want to say about:

- The time before we had consciousness, whenever that was. Say we get it at 6 months old as an embryo in the womb. Is that when we started existing? Not at birth and not at conception?

- Since we can’t remember our first consciousness, (at least most of us cannot — although a few claim they can remember being in the womb) does that mean that we are not the same person as we were in the womb? (It is hard to even state the question without some kind of paradox.)

- What about episodes of memory loss? If I get a knock on the head and lose memories of the past week, then am I the same person as the person who occupied my body during that week? If not, then who was in my body?

- If we get the technological possibility of copying the parts of my brain structure that make up my memory for some event E, and also get the technology to put that brain structure in someone else’s brain, so they can now “remember” event E, does that mean that they now become the same person as me? That’s what it seems his theory implies. If we can put the memory in 1000 people, then do I become the same person as those 1000 people? Could that make any logical sense?

These questions might be answerable, but it will mean making Locke’s theory much more precise. It seems that however we make the theory more precise, we will end up with some strange consequences that go against our “common sense” about personal identity.

Parfit

It has been the work of Parfit that has most dramatically challenged the way that philosophers think about personal survival through change, arguing that it is in fact a mistake to care about personal identity as such. Rather we should care about our projects and commitments, rather than our continued existence. He says that survival is not all-or-nothing, but rather can be a matter of degree. We can also survive to a degree in more than one body, and thus go on living as several different people.

Parfit’s work is relevant to Buddhist theories of the non-self, which have some similarity to Hume’s view. These say that the self is an illusion. Buddhists say we should give up worrying about the self or fostering the illusion of the continuing of the self over time. Hence they recommend living in the moment. But Hume, on the other hand, recommends giving up on philosophical thought and just relying on our natural instincts and habits.

Derek Parfit drew attention to the methods and goals of philosophical reasoning in his book Reasons and Persons. He distinguishes between descriptive metaphysics and prescriptive metaphysics. A descriptive approach aims to capture our ordinary ways of thinking and fit with our existing conceptual schemes. A prescriptive approach is called for if there is something problematic about our existing conceptual scheme. Parfit argues that our ordinary ideas of personal identity are inadequate and we need to change our conceptual scheme. He argues we should stop caring about personal identity altogether and instead care about the continuation of our projects and commitments.

Swinburne

Swinburne takes a very different view, arguing that we are essentially non-physical entities, and we have souls that are our essential being. This is obviously close to a religious view, but he argues for it using careful argument rather than appeals to faith or reference to sacred texts. His main idea is that physicalism cannot explain our consciousness, and the only way we can explain consciousness is to suppose that there must be a spirit that enables our minds to operate. He also adopts the view that that spirit is us — the human body is more like a temporary location where the spirit lives for a while. His latest book is Are We Bodies or Souls?. Obviously his answer is “souls”. (Some might say “neither.”) In the extract we have in the book he adopts arguments very similar to those of Descartes in the Meditations. The basic idea is that I am essentially a thinking thing, because I can imagine myself without a body but I can’t imagine myself without a mind. He concludes that we are essentially minds, and that we are not essentially bodies. This sort of argument has been analyzed a great deal, and can be doubted at many stages.

Williams

Bernard Williams was a British philosopher of the twentieth century. His stature as a philosopher seems to be increasing as people reflect on his work. In the extract we have, from The Self and The Future, his real focus is on how thought experiments work or don’t work. He uses a thought experiment in a science fiction scenario that leads readers to adopt one view of personal identity. Then he uses the same scenario but changes a few details that should be rather irrelevant, and says that now we are led to a totally different conclusion. This leads us to reflect on whether we can really rely much on this methodology, and whether our intuitions regarding these experiments are any kind of a guide to truth. His conclusion is mainly sceptical. It seems that the way we frame a thought experiment about what looks like body-switching has major effects on our intuitions about the cases. Thus, these thought experiments should not be considered a guide to the truth. Just because we can roughly imagine waking up in a different body does not mean that it is really a coherent and real logical possibility that illuminates our understanding of our true essence.

Module 5: Topic: What Is Race? What Is Gender?

Reading

Introduction

ANTHONY APPIAH, The Uncompleted Argument: Du Bois and the Illusion of Race 549 (Available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/1343460?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents — you will be able to access the full version through the university library).

SALLY HASLANGER, Gender and Race: (What) Are They? (What) Do We Want Them to Be? 560 (Full version here: http://www.mit.edu/~shaslang/papers/WIGRnous.pdf )

QUAYSHAWN SPENCER, Are Folk Races Like Dingoes, Dimes, or Dodos? 571 (Not available elsewhere. Spencer’s other publications are here: https://sites.google.com/site/qnjspencer/publications )

ELIZABETH BARNES, The Metaphysics of Gender 581 (Not available elsewhere.)

Resources

Race

1. Dr. Charles W. Mills – Does Race Exist?

7 minutes, excerpt from a lecture.

2. Radiolab on Race. Podcast.

3 separate pieces. I hour total.

Radiolab has a very distinctive and quirky approach in its style. This episode is interesting in the scientific study of race.

3. Do human Races Exist – with Professor Henry Harpending

Henry Harpending was an anthropologist who argued that race was real and was not just a social construct. So his views are rather controversial.

11 minutes interview.

4. Philosophers on Rachael Dolezal.

Philosophers on Rachel Dolezal (updated)

Several philosophers weigh in on this controversial case.

Gender

1. What is Gender Philosophy Tube. Talking head with some text added. 9 minutes. Lots of theory relating to Judith Butler.

2. Every Sex & Gender Term Explained . Guy at desk talking to camera. 10 mins.

3. Sex And Gender: What Is The Difference?

Written by Tim Newman

Sex and gender: Meanings, definition, identity, and expression

4. The 6 Most Common Biological Sexes in Humans

Blog. http://www.joshuakennon.com/the-six-common-biological-sexes-in-humans/

5. How Many Sexes Are There NYT, by Anne Fausto-Sterling;Published: March 12, 1993

Opinion | How Many Sexes Are There?

6. How Many Sexes? How Many Genders? When Two Are Not Enough by A. H. Devor, Ph.D.

7.Here Are the 31 Gender Identities New York City Recognizes

8. The Ultimate Transgender FAQ for Allies Rachel Williams | Musings from a Trans Philosopher

9. Transgender identities: a conversation between two philosophers

10. The idea that gender is a spectrum is a new gender prison

11. Ignoring Differences Between Men and Women Is the Wrong Way to Address Gender Dysphoria

12.Gender identity needs to be based on objective evidence rather than feelings

13. The existence of biological sex is no constraint on human diversity

14. Should Men Who Identify as Women Compete in Women’s Sports?

Let me know if these links don’t work.

Race and Ethnicity

Questions of race in the USA are of course very politically charged. In the main sources about science, I have provided the mainstream view that race is not biologically real. If you do some searching of the internet, you will find many views that disagree with this idea. Some of these are just plainly racist and hateful. Others are at least outwardly more scientific. For example, here is a video of Douglas Whitman.

He argues for “The Evolutionary and Biological Reality of Race”. https://youtu.be/jeb09GS7ids

He is retired from Illinois State University and he was an expert on insect ecology. Douglas W. Whitman

The video is posted by American Renaissance, which is commonly described as a white supremacist magazine. In the video, Whitman is introduced by Jared Taylor, the editor of the magazine. The Washington Post describes Taylor as a white nationalist.

Taylor has connections with Steve Bannon, Trump’s former chief strategist.

I should be very clear that I am not endorsing the views of Whitman and I certainly would condemn white nationalism.

It is also important to be very clear that the history of “racial naturalism” is almost always to a claim that some races are better than others, and an attempt to subjugate or eliminate “inferior races”. We see that in the history of slavery, the Nazi treatment of Jews, and contemporary racial hatred.

Nevertheless, it is not conceptually necessary that belief in the biological reality of race is linked to attempts to justify the superiority of one race over others. It could have turned out that race is a useful category in medicine, for example, and that doctors would need to take it into account in treating different people. But it seems that medicine does not need to consider race.

Given how politically charged the issue of race is, and how many problematic views are out there in print and online, you need to be careful in what sources of information you use. When citing sources, be careful in your assessment of what you bring in.

Supposing that it is true that there is no biological justification of categories of race, it remains a question whether we should keep using categorizations of race in social policy, job hiring, doing a census, in our personal lives, and in popular culture.

On the other hand, it seems that the scientific discussion is race is still developing. At some point in the past there seemed to be a scientific consensus that race is not a legitimate scientific category. Now there seems less consensus, and some scientists do think there is good evidence for a racial categories of humans.

As some have already noted, there’s reason to be worried about this because very often the motive of racial differentiation is to then argue that some races are superior to other races.

However, there are different possible reasons to preserve a concept of race. Here are 3.

1. Race is a useful category in medicine because some populations of people that correlate strongly with our notions of race are susceptible to some diseases much more than other populations.

2. People identify strongly with their race and take pride in it, and to deny that race exists would undermine that. This does not seem to require a biological conception of race though. Rather is only seems to require race as a social group concept. Exactly what we mean by race if it isn’t biological may not be very clear, and there are questions about what the criteria of race are then, and who gets to decide what race a person belongs to.

3. It is sometimes argued (by Kincaid, for example) that there are social divisions between races that are the result of racial discrimination — i.e. structural racism. He argues that we can’t understand racism unless we have a category of race. Again, this is not a biological concept of race, but rather a social group concept.

I’m tempted to say that race is inherently a biological concept, and that to say it can be non-biological is a mistake. When we talk about groups like Asians, Caucasians and Native Americans, these are much more ethnic groups (which may be sometimes characterized by superficial differences such as skin color, hair color and texture, and facial features) rather than biological groups. But it is tricky to analyze our concept of race.

Sex and Gender

It will be important for students to understand the (purported) distinction between sex and gender, which was especially prominent in the work of the French philosopher Simone De Beauvoir. The basic idea is that sex is biology while gender is psychology. The traditional assumptions of medicine and conventional thought has been that biology is the dominant category and that psychology should follow biology. I.e., your sex is determined by what genitals you have and your self-understanding about that should be determined by your biology. This sort of approach then often gets used to say that women’s natural function is to give birth and so their main role in life should be as mothers. But it does not have to be taken in this direction.

In the last few decades biologists have pointed out that it is simplistic to say that there are just two biological sexes. There are a significant number of people who do not fit in with either the biological sex of male or female. Sometimes people like this are called “intersex.” In the past, there was a lot of social pressure to make them either male or female, either by surgery or by pushing them into predefined gender roles. These days there is a movement away from this. It has been pointed out that while intersex people are different, there is nothing biologically wrong with them: they just don’t fit with people’s expectations.

The idea of gender is harder to define that sex. It gets many different definitions. It can include both your self-image and how society defines you. It can include body image, clothing, styles of dress and self-presentation, behavior roles, sexual preference, self-naming, and how you are categorized by various bureaucracies. Traditionally there have been just two genders, male and female. But now there are moves to increase the number of genders. There are enough variables to make the number of possible genders infinite.

There is the question of whether it is possible to change one’s gender. This is partly an empirical question. Some people say they are gender-fluid and move from one gender to another depending on a variety of factors. Other people say their gender is fixed, and no amount of psychotherapy or training will change their gender. There have been many cases of young people whose parents wanted to change their gender through raising them as the desired gender, but there have been no reports of success in doing this. It seems that it is as impossible for other people to change your gender as it is for them to change your sexuality. But it is still possible for other people to have variable gender and sexuality.

The phenomenon of transgender people has become much more prominent in recent years. There has been plenty of press coverage and you can find many videos on YouTube by and about transsexual people especially children. It is important to remember that this is still not a well-understood phenomenon — psychiatric experts still have little explanation of why it happens or even what it is. They have only a vague idea how to help people, although the standard approach these days seems to be to allow adults to get gender-reassignment surgery if they want it. It does seem that giving people what they want reduces the suicide rate. There is much more debate about whether to encourage young people in their beliefs that they are a different gender from the one assigned at birth. It does happen that young people are allowed to identify as a different gender at school and at home, and to dress accordingly. Some of the debate has been about whether they should play on male or female sports teams, which locker rooms they should use, and which bathrooms they should use. There’s also debate about biological interventions such as hormone blockers which delay puberty, hormone supplements to change the physical features of the young people, and then surgery to prevent breast growth or give breast implants, and changes to genitals.

So there is a great deal of debate in psychology, medicine, and sociology about what we mean by gender and how essential it is. We can identify some positions.

- Eliminativism. There is no such thing as gender. There is only biology. We should stop encouraging people to think about gender as a separate category than sex. It tends to be skeptical about traditional gender roles.

- Biological Essentialism. Gender and sex are the same thing. This is actually not very different from eliminativism, since it also moves away from any independent notion of gender. But while eliminativism is skeptical about traditional gender roles, essentialism tends to endorse them.

- Social Constructionism: Gender is different from sex, and is socially constructed. On this view, gender categories are roles we can choose to take on, although it may take a good deal of practice to learn how to follow them convincingly. On this view, gender roles are fine so long as they are good for everyone, but they are not good if they take away people’s freedom.

- Psychological Essentialism. On this view, gender is a psychological state that one cannot often cannot choose or reject. It is just one’s nature, and one is born with it. But it is not reducible to genetics or anatomy. Gender is a distinct psychological condition.

These may not be the only position, and indeed they may be problematic. There are at least some empirical issues here that would be relevant to the philosophical issues. We would want to know whether people can genuinely change gender, or be gender fluid, or whether it is true that people’s gender is fixed no matter how much we try to change it. We might also want to know whether people do better with traditional gender roles or whether they flourish more if our society gives more freedom.

The philosophical and ethical issues are about whether we should take gender seriously or whether we should be suspicious of it, especially in the context of those who say that they want their bodies changed to align with their gender identity.

Transgender

The question of transgender, trans, or sex change is a major one these days. There are metaphysical issues, but they are closely related to psychology, law, and ethics.

It’s in the news a lot of the time. In 2018 NY State created a new category for gender on birth certificates and allowed people to self-identify their own gender.

New York City Creates Gender-Neutral Designation For Birth Certificates

Today’s news is that “‘Transgender’ Could Be Defined Out of Existence Under Trump Administration”

The UK Government has initiated a public debate over proposed changes to the Gender Recognition Act. https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/reform-of-the-gender-recognition-act-2004

There is a lot of debate over whether people should be able to self-identify what gender they are for legal purposes. The debate has been fierce.

‘Shifting sands’: six legal views on the transgender debate

So there is no shortage of controversy. This is not an ethics course, and so our aim is not to get into the ethics of the debate. We can agree that it is good to treat people well and to protect vulnerable populations. But there may be different vulnerable populations with competing interests.

There are metaphysical issues here:

1. Is the category of gender a valid one we should use to classify people, rather than using biological sex?

2. If so, what criteria should we use to decide gender if they are not biological?

3. What genders are there? Male and Female, but what others?

Once we separate out biological sex and psychological gender, then it is hard to see what else gender could be apart from outward behavior, forms interpersonal relationships, and inner feelings. For practical purposes we may need to pay attention to the possibility that some people might lie about their real inner feelings for ulterior motives, but that worry may also be exaggerated. There is also a possibility that people may be confused about their inner feelings since once removed from biology, gender is confusing. But bracketing those concerns, we can still ask in an ideal case what would decide a person’s gender.

Is there a feeling of being a woman or being a man, being female or male, that is independent of having a conception of one’s body and what gender is assigned to you by others? Many people say so, and not just transgender people. Aretha Franklin sang “You Make Me Feel Like a Natural Woman.” There is plenty of psychological study of gender roles but we also know that they are shifting dramatically and have never been static. People used to make heterosexual assumptions about gender, but now we accept that there is no particular connection between one’s gender and one’s sexual orientation.

Yet it is extremely difficult to identify what it is to feel like a man or a woman other than filling certain social gender roles or having a belief that one is a man or a woman. But feeling that you are X and believing that you are X seem to be very different, because normally a belief can be mistaken. If all we have to go with is the belief, then

“I believe I am a woman” guarantees its own truth

That’s an unusual sort of belief. We normally expect that there are independent criteria for the truth of a belief. If there are not, then it’s its unclear what to make of it.

Still, that’s not an argument against it. Maybe more confusing to me is if there is an inner feeling of gender, what that is. If other people have an experience of it, is it possible to explain except by saying that “I feel like a male”? I have to say I’ve never seen that explained.

So if we are going to completely separate gender from sex, then it doesn’t seem like a well defined category. There’s nothing much to limit proliferation of different categories of gender. Maybe that’s a welcome result.

Another possibility is that we should take an eliminativist view about gender in the same way that Anthony Appiah is eliminativist about race. He thinks it cannot be done overnight, but may take hundreds of years. Maybe we should aim to downgrade gender in the future as an important category and make it less of a part of our self-conception.

Notes on the readings

Haslanger

There is a useful summary of Haslanger’s view of gender here, co-authored by Haslanger. Her account of gender does not aim to capture the subjective experience of being male or female. Her goal is to have categories of gender that are helpful in understanding the oppression of women. Here is her rather technical definition of being a woman:

S is a woman if and only if

- S is regularly and for the most part observed or imagined to have certain bodily features presumed to be evidence of a female’s biological role in reproduction;

- that S has these features marks S within the dominant ideology of S’s society as someone who ought to occupy certain kinds of social position that are in fact subordinate (and so motivates and justifies S occupying such a position); and

- the fact that S satisfies (i) and (ii) plays a role in S’s systematic subordination, that is, along some dimension, S’s social position is oppressive, and S’s satisfying (i) and (ii) plays a role in that dimension of subordination.

Haslanger is happy to admit that there are other definitions of gender that may be useful for other purposes. Her analysis depends on the assumption, which she defends with reference to other theorists, that women are oppressed in all human societies. As a feminist, she wants to end gender hierarchy, so it follows that she wants both men and women in her senses to stop existing. There would be no men and women in a non-hierarchical society, on her definitions.

One question for Haslanger’s approach is whether it would be useful and to whom? We can imagine a parallel definition of race, which defines it hierarchically. It would hardly be very helpful in distinguishing between different races, especially in helping us understand some minorities who are not in a subordinate position in society. Are all women in our society subordinated because they occupy a female role in society? That’s not so clear. It would need more discussion. The definition does not prove that there is oppression and so it is not so clear what work it does.